Every year, Canadians doing their laundry are responsible for releasing 1,465 tonnes of microplastics into the environment, a new report has found.

The number, published in a report backed by Environment and Climate Change Canada, is the latest effort to quantify how plastics are radically reshaping the Earth’s oceans and lands. It comes as countries around the world meet in Busan, South Korea, for a fifth round of negotiations aimed at curbing plastic pollution.

When the production of plastic shot up in the 1960s, the fossil fuel-based material was hailed as a wonder material capable of creating a whole new generation of consumer products — from plumbing and plastic bags to medical devices and the U.S. flag Neil Armstrong planted on the moon. But it was also quickly recognized as a global problem, and since then, the accumulation of plastic debris has only grown amid booms in the production of electronics and textiles.

“The tsunami continues. We have more and more plastic production. It's doubling every 15 years,” said Peter Ross, a senior scientist with Raincoast Conservation Foundation who co-authored the report.

By the early 2000s, scientists started to recognize the reach of plastic pollution extended far beyond what could be easily spotted with the human eye.

Since then, microplastics — defined as plastic particles less than five millimetres long — have been found in nearly every ocean, terrestrial environment and species on the planet.

In recent years, plastic produced for the Canadian market has outpaced economic growth and has more than tripled population growth in recent years, according to Statistics Canada. As the annual amount of plastic produced for Canadians now weighs more than the Great Pyramid of Giza, much of that has dispersed into the environment.

“We've had 23 or 24 years where hundreds of studies have been published around the world detecting microplastics in everything from air to water to sediment to zooplankton to shellfish, salmon, whales, blue whales in the Arctic,” said Ross. “Basically, everywhere.”

Ocean plastics found everywhere in Canada

The latest report analyzed more than two decades of research looking at microplastics, with a particular focus on how they have accumulated across Canada’s lands and waters.

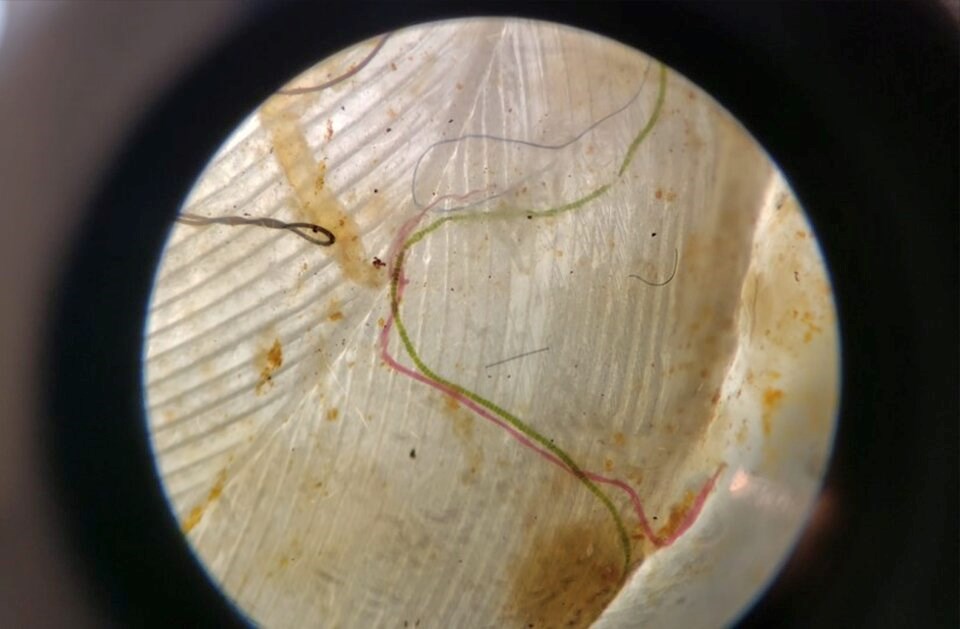

One 2021 study that used ice-breakers to sample Arctic waters found microplastics in 96 out of 97 samples. When Ross and his colleagues took a closer look, they found the multicoloured samples were polyester fibres.

Anna Posacka, the report’s lead author and a strategic advisor with Ocean Diagnostics Inc., pointed to studies finding plastic microfibres in everything from the fish of the Great Lakes to zooplankton and wastewater in British Columbia.

In B.C.’s Straight of Georgia, for example, microfibre concentrations have been found to hit 3,200 per square metre of seawater — nearly 70 times more than in samples Ross analyzed in Arctic waters.

Health effects of microplastics not fully understood

Research has found microplastics are inhaled, absorbed through the skin and consumed through food and water — all eventually ending up in our lungs, livers, kidneys and even placentas.

Ross said once inside an animal, studies have found plastic pollution can block intestines, or inflame the gut.

One 2023 survey of current research into the human impacts of microplastics found evidence of chronic disease, DNA damage, organ dysfunction, metabolic disorder, neurotoxicity, and reproductive and developmental toxicity, among other effects.

One 2021 study in the United Kingdom found ingesting or inhaling high levels of microplastics in contaminated drinking water, seafood and salt may lead to cell death and allergic reactions.

In an Italian study published a year later, researchers examining the breast milk of 36 women found microplastics in over 75 per cent of the samples. Patient data showed no links between the presence of microplastics and patients' age, use of personal care products, or food consumption habits.

Their conclusion: ubiquitous microplastic presence makes “human exposure inevitable.”

“There’s a lot of concern that we're getting exposed chronically through breathing, drinking, eating, and these particles are floating around our system,” Ross said.

“We have to look at sort of a weight of evidence from different approaches. But the exposure is, shall we say, ubiquitous all over the world.”

An at-home solution

Microplastics come in all shapes and sizes, from granules and pellets to flakes and beads.

Taken together, however, the report found 80 per cent of all microplastics found in Canada are fibres shed from textiles or clothing when passed through washing machines. The nearly 1,500 tonnes of microplastic added by Canadians every year is equivalent to the weight of nearly 5,500 grizzly bears, note the researchers.

“My laundry and your laundry, everybody's washing machine is shedding fibres, millions of fibres every single time we wash,” said Ross.

A single load of laundry can release up to 17 million microfibres weighing about 135 milligrams, according to Posacka.

But wash that same load of clothing in cold water and hang it to dry, and you can drop the number of microfibres shed from your washing machine by up to 95 per cent.

That number also depends on buying durable clothing, washing less, using a front-loading machine and washing full loads on gentle cycles, Ross said.

A call for regulation, education and diplomacy

It’s a recipe for environmental protection the scientist says is well developed in education campaigns in places like Metro Vancouver. The regional body’s wastewater treatment plants tend to capture up to 95 per cent of microfibres flushed into sewers.

Unfortunately, says Ross, many of the microfibres still make it to sea. Those captured by wastewater facilities often end up on farms and forests across Canada in the form of recycled biosolids. From there, the plastics can end up in food at the grocery store, said Posacka.

The report says there are big blind spots on just how much plastic pollution is coming from several sectors, including commercial laundry, maritime effluents and textile manufacturing.

It targets a global textile supply chain that often uses the worst plastic fibres in weaves more likely to shed into the environment.

The report calls on the Canadian federal government — which is currently charting a road map to reduce microplastics — to advance its plans to regulate the textile industry through performance standards and move away from a culture of ‘fast fashion.’

That’s where a throwaway cycle of consumption “promotes the rapid production of cheap, trend-driven garments” without adequate recycling systems in place, the report notes.

“If Canadian retailers are importing products that are harmful to the Canadian environment, there are ways for Ottawa to intervene in that,” said Ross, pointing to domestic regulations and negotiations currently underway in South Korea.

“I'm a big fan of treaties, and I've seen where they've worked very well to protect the tragedy of the commons.”

'Don't have to wait' for companies, governments

Another technological solution in the report cites two appliance companies, Samsung and Grundig, who have introduced filters into their machines to catch microfibres before they reach the drain.

France has already mandated every new washing machine sold on the market by 2025 be equipped with a similar microfilter. Posacka said it’s one area where Canada could also take the regulatory lead, perhaps offering tax breaks for companies who follow suit, or penalties for those who don’t.

“That’s one important piece of legislation that can make a difference,” Posacka said.

When it comes to individuals, Posacka suggests consumers choose clothing companies that have a record of actively reducing microplastics in their supply chain.

For Ross, the best thing a motivated household can do is not to wait for companies. Instead, he said, buy and install an effective washing machine filter, Depending on the model, it will curb microplastic pollution by up to 95 per cent on its own.

“They cost somewhere in the neighbourhood of $150,” he said. “That's the number one thing you can do.”

“Consumers don't have to wait.”