Colten Lefthand, an Eden Valley resident and member of the Bearspaw First Nation, climbed into the saddle as a small child, putting him on a trail that would not only take him to new heights, but give him new direction back home.

Lefthand began roping in 2009 as a junior breakaway roper in the Indian Rodeo Cowboys Association (IRCA) before going on to team roping as a heeler — the roper that lassos the hind legs of a steer.

In October, he competed in the Indian National Finals Rodeo (INFR) in Las Vegas, winning a round among the best in his sport.

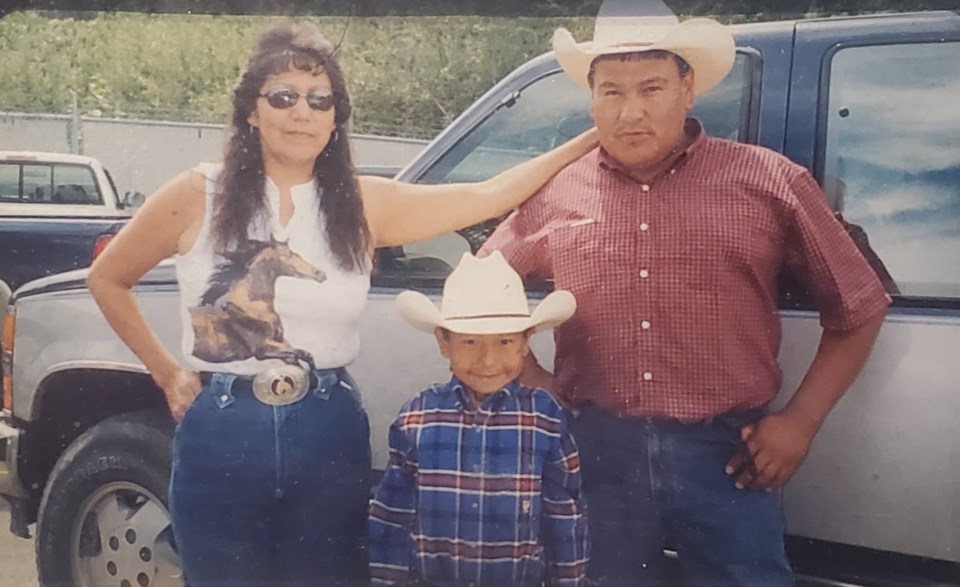

The path to that success began years before, with his father Keith and mother Jamie both accomplished rodeo athletes themselves.

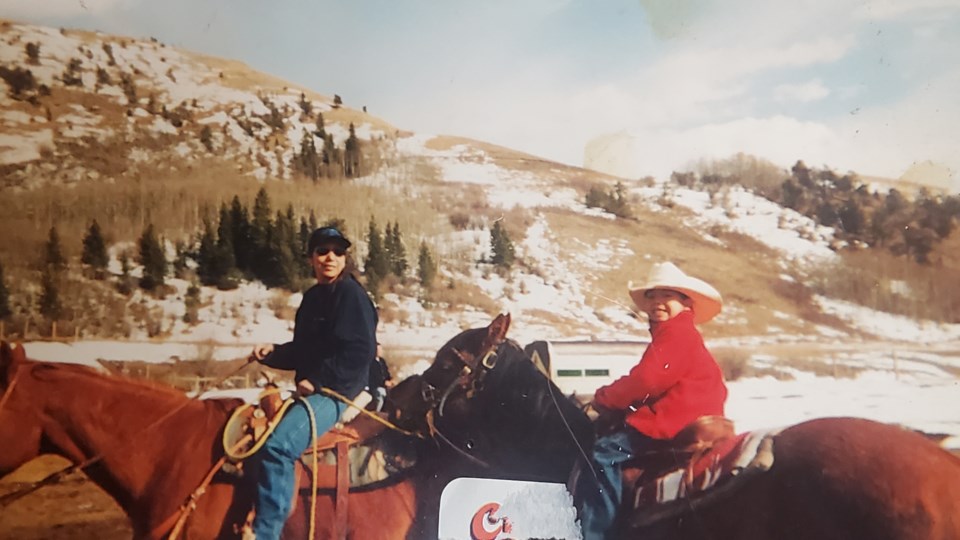

“My dad and my dad’s dad rodeoed. His dad grew up on a ranch and my dad rodeoed his whole life — still does,” the 27-year old team roper and father said. “My mom barrel raced when she was younger.”

That does not mean their children — of which Colten is the youngest — ever felt obligated into the sport.

“My parents never pushed any of us into rodeo, just let us do what we wanted to do,” he said.

One brother, Cody Lefthand, is a filmmaker and on the board of the Calgary Society of Independent Filmmakers, while another, Kenton, is a hockey player in British Columbia.

“So I was the youngest, and I think that’s why I picked up roping — I was always at the rodeos,” Lefthand said. “And then I just started making friends that rodeoed, and I’d always look forward to going to the rodeo to hang out with my friends. Then one year, I just wanted to do it.”

That’s not to say he didn’t know the ropes already.

“I always knew how to swing a rope and ride a horse, because it’s how I grew up, but I never really wanted to compete,” he said. “Then I remember the day, at the Tsuut’ina Agriplex, they had a team roping jackpot my dad roped all the time, then after my dad asked if I wanted to rope too.”

It was actually Lefthand’s friend from hockey that took to it at first.

“He really wanted to do it, then I wasn’t just going to sit there and watch my buddy learn to rope,” he recalled. “Then it was really fun, and after that I started getting into it.”

He had caught the bug, said Lefthand’s father.

“He just picked it up really fast compared to boys that are a year or two years older,” Keith said.

Watching his son grow, he promoted patience and hard work.

“I told him you have to take care of yourself,” he said. “You just keep practising, you just keep catching, and the good headers are going to see you.”

Lefthand kept at it, practising year-round.

“We made a roping dummy with two-by-fours, and he’d be out there in the nighttime roping at night,” Keith said. “In the wintertime, we would clear an area and he’d still be roping.”

“He got to where some of these better headers are starting to notice that maybe it wouldn’t hurt to rope with Colten.”

That began with junior breakaway roping, where a small calf is lassoed and the rope breaks away from the saddle upon success.

“So, I did that the last two months of the rodeo season, then the next year I turned 16 and there was some big controversy in the association where they changed the age group to 15 and under to be in junior events,” Lefthand said.

This meant jumping into the deep end for the then novice roper.

“I lost a year to try to enjoy my junior career, but when I look at it now, it kind of helped me being a kid having to rope against men,” he said. “I didn’t win nothing, but I think it taught me a lot. It taught me how to lose.”

The following year, as Lefthand turned 17, they changed the maximum age back to 16.

While they never pushed, once he embraced the sport his parents were behind him.

“Looking back now, there’s this whole appreciation of my parents, all the stuff my parents ever did for me, supported me,” he said.

“That year, my dad took me to rodeos, paid my entry fees every rodeo knowing I wasn’t going to win a dime, but he still supported me because I wanted to do it.

“That’s the biggest thing in rodeo, having support. Especially coming out from Eden Valley, I could very well be like anybody my age out there that’s not doing good.”

That good fortune and opportunity is not lost on him.

“It’s not an easy place to grow up, that’s for sure. You type Eden Valley in on Google and it takes a while until you get positivity,” Lefthand said. “I don’t know if people know how tough it is because of how isolated everyone is.

“But at the same time, there’s a lot of benefits to it too, like I think it’ll make you tougher living out there.”

Years later, Lefthand found himself in the top standings with his heroes at the INFR.

When he found himself short a partner for a qualifier, he learned by chance four-time world champion Nolan Conway was looking for a heeler.

“I called Nolan and he said, ‘It works out perfect, I need another guy,’” Lefthand said. “Then at the rodeo, we drew a good steer, he turned him for me, and we ended up winning that rodeo.”

The two then went on to the INFR in October.

There, Conway and Lefthand won Round 3 with a time of 4.55 seconds on Oct. 22, neck-and-neck with Round 1 winners Derrick Begay and Ty Romo with 4.63 seconds and Round 2 winners Erich Rogers and Aaron Tsinigine with 4.87 seconds.

While Rogers and Tsinigine went on to finish in the Saturday final with a time of 3.55 seconds, seeing his name among his heroes was a milestone for Lefthand.

The mark it made on his life is one his family is grateful for.

“It honestly is the best life and it’s crazy. My mom tells everyone to get into rodeo, because it’s a good life,” Lefthand said. “She knows I’m safe, she knows she doesn’t have to worry about me.”

This all despite the financial imposition.

“You spend so much more money than you win, there’s nobody that rodeos that’s up money-wise right now, but it’s not even about that. You meet way more nice people than bad people in rodeo — it’s the friendships and everyone’s a family.

“I have friends in every state that would help me out if I ever needed, and it’s just the way of life with rodeo.”

Despite that, the heeler still needs to work a day job to support his dream.

“The goal is to do it for a living, but right now I have to have a job working at the Eden Valley public works,” he said.

The heeler considers himself lucky to have a steady job driving the water truck delivering to Eden Valley’s homes.

Around 80 per cent of the reserve’s residents are unemployed — a number not helped by lack of education or training, Lefthand said.

When he was younger, Lefthand said he wanted to escape Eden Valley, but that changed.

Crediting rodeo and horsemanship with keeping him away from drugs and other problems he saw growing up, he was drawn back in hopes of starting a grant-funded program teaching youth horseback riding.

“That brought me back to the community because I think I matured and realized if I did that program, I could get the youth out there into rodeo,” he said.

“My dad would tell me lots of stories about Eden Valley and how everyone out there used to rodeo.”

His father agreed that the pursuit, and working with animals especially, helped enrich his son’s life.

“Every child should pick up a sport, but rodeo is special,” Keith said. “When you rodeo, your rope horse is probably your best friend.

“Horses are part of our lives. We believe the spirit of a horse helps a person in life in general, but if it wasn’t for (Colten’s) roping, and rodeo in general, I think the chance would be much greater that he could have gone on the wrong path.”

Lefthand’s mother Jamie, a former barrel racer, recalled how many homegrown competitors she was up against.

“I remember counting and there were past 50 barrel racers in Eden Valley,” said Jamie, who added her son is an exemplar to the children in the family.

“It would be awesome if Colten follows that dream and it becomes a reality. There are so many kids like my granddaughters. They want to be like barrel racers, they want to rodeo, they want to be like Coco (their name for Colten).”

While the grant funding disappeared at the start of the pandemic, the motivation for Colten remains.

“My main goal is to get that back, to learn how to properly fund it and get that going so I could get the youth into rodeo,” Lefthand said.

Since having a son of his own, three-year-old Cresten, Lefthand has an even greater drive to be his best.

“My son’s the biggest thing in my life, my reason for anything, why I get up every day and work hard,” he said, adding while now separated, he met Cresten’s mother through rodeo.

“I wouldn’t have my son if it wasn’t for rodeo.”

While Lefthand said he considers himself fortunate, he has still encountered racism and prejudice in his life.

“The first time I ever experienced racism was in minor hockey,” Lefthand said. “It was after a game we won and I had scored two goals, then we were shaking hands with the other team.”

One of the other players called him by a racial epithet.

While he said he let that slide off as a kid, the everyday racism he encounters today is more problematic, especially with police.

Lefthand said before registration stickers changed this year, there was an annual phenomenon in Turner Valley.

“There’s a lot of Lefthand’s in Eden Valley and our plates expire July 1, so every year, on Aug. 1, you’ll be driving to town, a cop will see that you’re native, turn around and follow you to make sure your plates are up to date then turn around,” he said. “It’s happened probably five times in my life.”

“Racism exists in rodeo, too,” he said.

A friend of his had a scab on a horse reopen during a jackpot event — a standalone roping event. This caused minor bleeding.

“There were two kids behind him, and I was behind them,” Lefthand said.

The two proceeded to make racist remarks about the roper, not knowing Lefthand was behind them.

“I heard the one kid say, ‘Well what do you expect, he’s a ****ing Indian?’” he recalled. “Then I said, ‘Did you just say what I thought you said?’ And they walked away.”

While initially angry, Lefthand said his friend calmed him down and they decided to let karma run its course.

“The funny thing is those kids knew I heard and it was probably in their head all day —roping’s all a mental game,” he said. “It probably wasn’t a very good feeling, because they roped like sh*t after that.

“That friend that they insulted, he won the roping, took their money and everything.”

The owner of the arena reached out personally wanting to know who made the remarks in the interest of banning them, Lefthand said, but he declined to give names believing they learned their lesson.

As a knowledge keeper who has been hosting non- Indigenous visitors at his home for information sessions, Keith said the path to fighting racism is building bridges and breaking stereotypes.

“The stereotypes have to change,” Keith said. “They need to know who we are, and I think once they do, it will get better as we go.”

Lefthand’s parents are proud and grateful for his most recent success.

His mother Jamie, while anxious, was overjoyed to see Lefthand take the round at Vegas.

“I was so proud of him, also nervous and anxious for him and praying for him, but as a mom, you just want your child to succeed in whatever they want to try,” Jamie said.

For Colten, the path has been a good one.

“It’s just a way of life with rodeo and it’s changed my life,” Lefthand said. “I’m thankful for it and I’m thankful for my mom and my dad for getting me into it.”